In spite of the development of interesting teaching materials by various people it remains the poor relation of language teaching, poorly related to the rest of what happens in the language classroom. I want to suggest two reasons why I think this is, and two corresponding ways of overcoming this and moving forward. In the second article I will pick up on the practical side of this and explore a strategy for action in the classroom, for laying the foundations of a mutually enriching integration of pronunciation with the rest of language. I intend to keep the concerns of NNS (non native speaker) teachers very much in mind, though I hope this will apply to pretty well everyone.

Is pronunciation the Cinderella of language teaching?

While much has changed in the last few decades in how we teach grammar, vocabulary, collocation, context and meaning I suggest that pronunciation is still rooted in an essentially behaviourist paradigm of listen, identify, discriminate and repeat. This is not wrong, simply insufficient, and so for most students and probably most teachers pronunciation remains a mysterious zone where the rules are not clear and it is difficult to make progress, or even to know if you have. Teachers do their best to integrate pronunciation but for many it remains a supplement to the main diet of most lessons, often relegated in lessons and course books to 'pron slots'.

I light-heartedly refer to pronunciation as the Cinderella of language teaching to conjure up a journey from neglect and separation to inclusion and integration, because my experience is that as we explore the two problems and develop solutions something remarkable can happen in terms of engagement for learners, impact across the 'whole' of language learning, and the feeling of enjoyable, do-able progress. So, what are the two problems and the two ways forward?

The need for physicality

The first problem I identify is that we do not sufficiently embrace in our teaching the physicality of pronunciation. While grammar and vocabulary can somehow take place in the cognitive realm, pronunciation is the physical aspect of language and needs teaching as a (subtle) physical discipline involving the muscles of articulation especially in throat and mouth. We give models but students can’t locate the muscles they need to change the sound they are making, to escape the grip of their mother tongue phonetic set. In short, they can’t find the internal buttons to press to get a different sound.

When you teach gymnastics or dance there is a focus on connecting attention to finely tuned muscular movements. In the case of pronunciation too we must help students to reconnect with the muscles that make the difference. So, my first task with my new learners (beginners, intermediate or advanced, teacher or student, native or non-native English speaker,) is to help them to (re-)discover the main muscles that make the pronunciation difference, to locate the internal buttons that trigger the muscle movements. At the beginning I find it enough to help them identify four such buttons (physically, not just cognitively) which enable them to get around the mouth and consciously find new positions of articulation. These are:

- Tongue (forward and back)

- Lips (spread/back and rounded/forward)

- Jaw + tongue (up and down)

- Voice (on or off)

This is the basic kit for navigating round vowels and diphthongs, and it transfers well to consonant sounds with the addition of relatively easy landmarks such as teeth, lip and palate. Learners experience a liberation once they develop conscious contact with these four movements and can start to move themselves, clumsily at first, around the territory which is conceptualised on the chart/map and actualised in the mouth. And there is a bonus, which is that muscles work by moving and much of that movement is visible. That’s why deaf people in every language can see what their friends are saying. So if we start to teach to this visibility of pronunciation we can enrich and support the physicality still further. It’s like learning to dance by watching it: the eyes can inform the muscles direct, without a need for cognitive explanation.

The need for a mental map

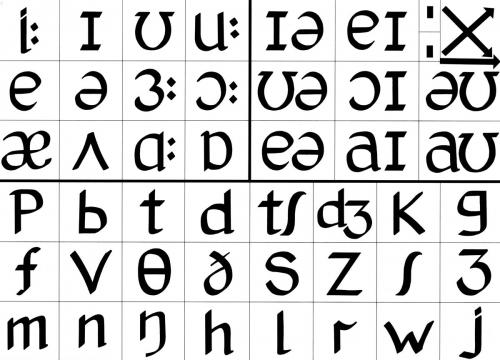

The second problem is that many students and teachers do not seem to have a clear mental concept and sense of direction. They lack a mental map to guide them through this unknown pronunciation territory and to complement and help conceptualise the physicality. For me the phonemic chart substitutes such a map for the mysterious and fearful void that many navigate by at the moment. The chart I use is different from most in that it provides a map, mental scaffolding and more:

It is a map with a geography, containing embedded information on WHERE & HOW sounds are made. And it is a MAP not a LIST of phonemes.

The arrangement of sounds on this chart tells you about how to make them.

The chart itself becomes a worktable, a place to enquire, diagnose and experiment, and where sounds connect into words, where mistakes can initiate successes.

The whole pronunciation syllabus is there in one single gestalt. The chart is always visible, and it is finite.

Just to illustrate briefly one of the information strands threaded into the chart: look at the chart and you can see the twelve vowels in the vowel box in the top left quadrant. The left side of that box represents the front of the mouth. The right side represents the back. The top of the mouth is the top of that quadrant and the bottom is the bottom. So straight away you can see the high and low vowels, and the back and front ones, and the central pair. And the neighbours in the chart are more or less neighbours in the mouth too. Now look at the first two rows of consonants just below, and again the front consonants are at the left, and the back ones are at the right. And generally speaking front sounds are the ones that are more visible! Neat isn’t it? Well there is much more in there, but this is what I mean by a map, and this complements the physicality which I will discuss next time, but which you can preview at the link below.

In conclusion

I am proposing that by using a mental map and by making pronunciation physical we can make it purposeful and engaging, and lay the foundation for learning an integrated whole. I look forward to your views and questions.

Links

- For a guided tour of the chart and introduction to the physicality go here and you’ll see it in the 2010 archive section about halfway down the page.

- For extracts from my pronunciation workshop with teachers go here: www.youtube.com/macmillanelt

Comments

On pronunciation

I am delighted to have the possibility of interacting with Adrian Underhill. Thanks to your "Sound Foundations" I had the chance to succeed and enjoy the phonology examination I had to take for the Licentiate Diploma in TESOL!

I agree that pronunciation is usually neglected, but I feel that on many occasions it is due to the lack of confidence we teachers have or the feeling that pronunciation "is not that important, and there are so many other areas we need to cover". But I'm sure many people will agree with me on how nice it is to have learners with nice pronunciation!

I feel the word "awareness" is a key word in all this and that pronunciation has to do with all aspects of the language, not just to speaking as some might think. If learners are not aware of, for instance, the fact that native speakers include intrusive or linking sounds in their speech, they might not fully understad the listenig material the teacher gives them. If we don't read something adequately with the right pauses we might fali to understand the text.... and how many times do our Spanish speaker students confuse too and to, can't there be a lack of awareness of pronunciation of those words which then might lead to their misspelling the words?

Just a few thoughts to contribute to the discussion!

Cheers from Uruguay!!!!!

Laura

I know it's going to be a good start to my phase three of learning English. Thank you.